I can't believe it's not you

| Gallery

Charlie Hamish Jeffery

I can't believe it's not you

Charlie Hamish Jeffery

I can't believe it's not you

Charlie Hamish Jeffery

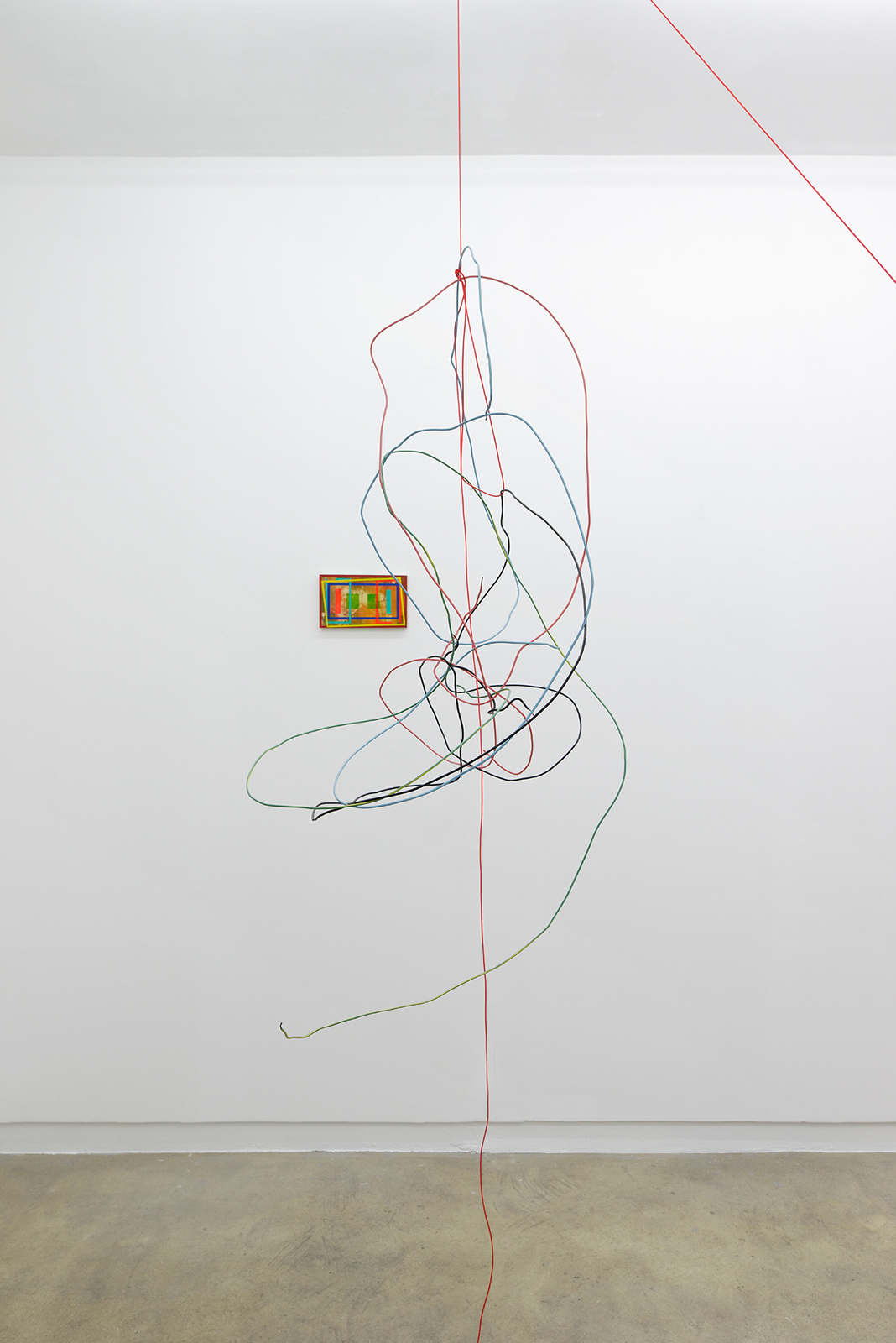

Exhibition view

I can't believe it's not you

Charlie Hamish Jeffery

Exhibition view

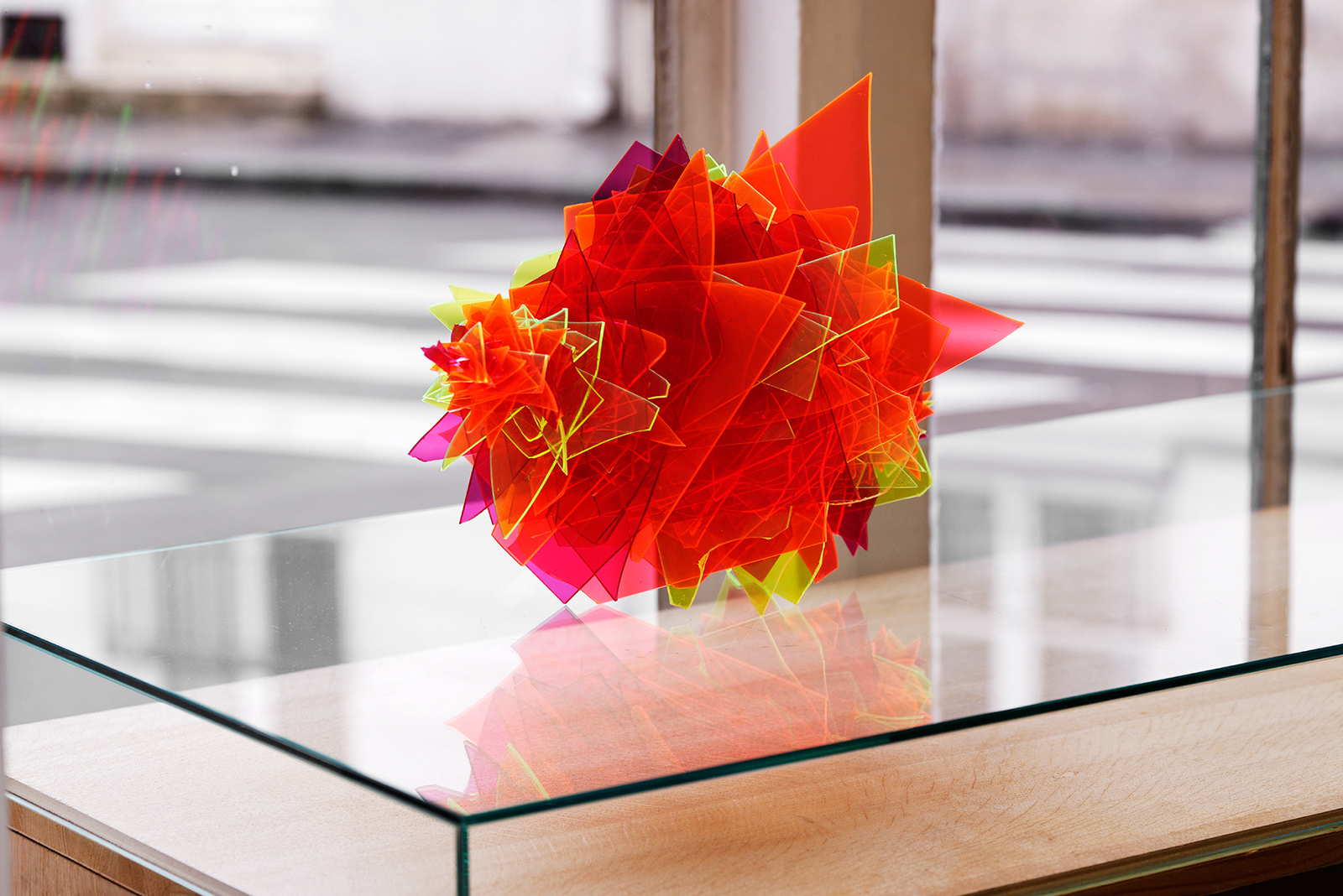

I can't believe it's not you

Charlie Hamish Jeffery

Exhibition view

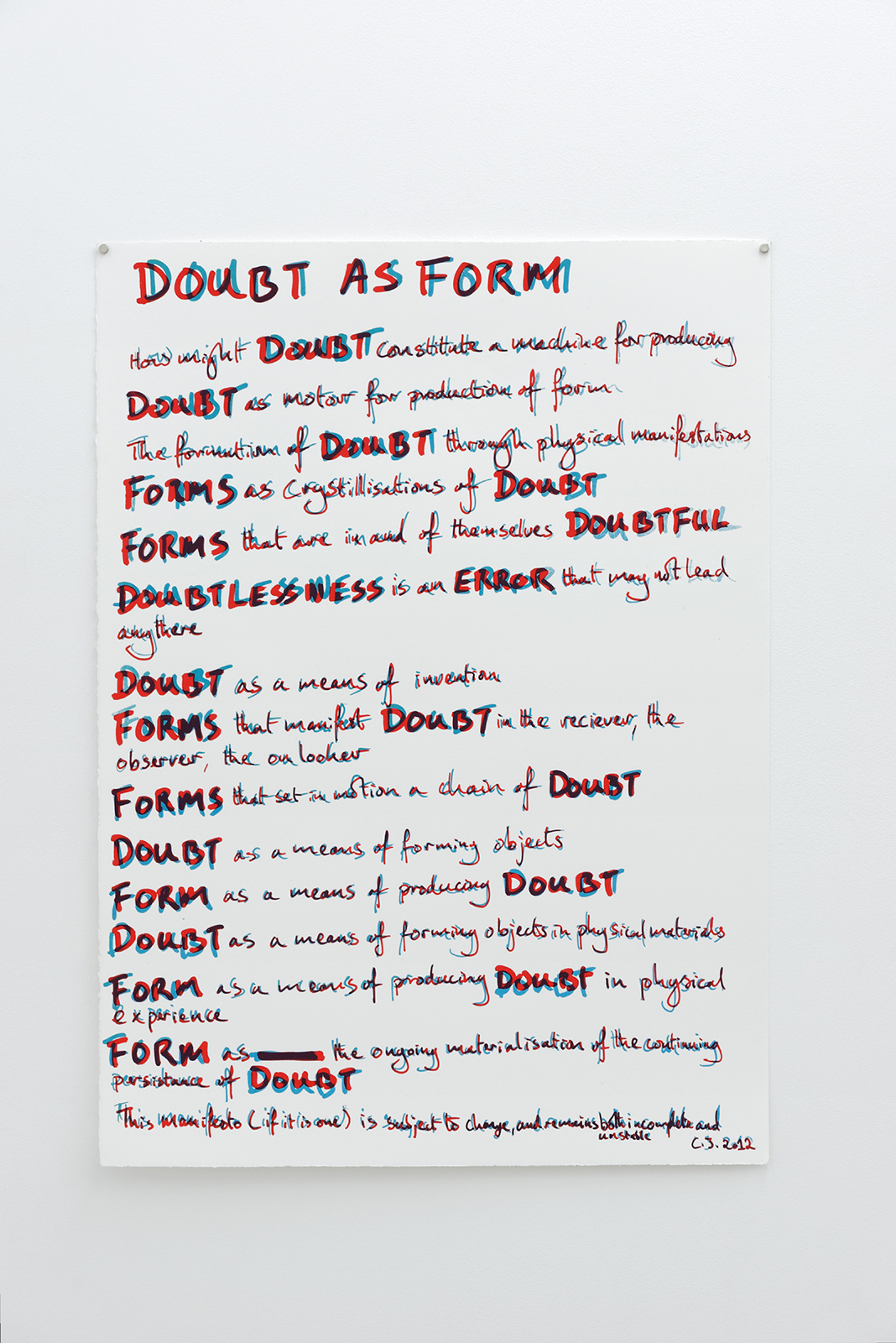

I can't believe it's not you

Charlie Hamish Jeffery

Exhibition view

I can't believe it's not you

Charlie Hamish Jeffery

Exhibition view

Acrylic on poplar plywood

Unique artwork

acrylique sur plexiglas

Unique artwork

clothesline, electrical wire, metal hook, duct tape, acrylic paint, plywood, screws, pants

Unique artwork

Acrylic, oil and plaster on advertising glued on mdf

Unique artwork

EN

Revolution of the humble

I have known Charlie Jeffery since 2006, the year of my first project as a curator. Later on, we worked together again when my research focused on a classic figure of 19th-century Russian literature: The idle aristocrat Ivan Goncharov describes in his novel Oblomov. At the time, I fantasized about the possible definitions of the word “inertia”, believing it would reveal more obscure and fanciful meanings if I dragged it in the wake of fictional characters trapped in a maze of negation—Bartleby at the head of this brotherhood of the lame, or the wise. While putting together an essentially fiction-based collection of books on the topic, I was looking for artists who could concentrate their production on what I see today as an expression of active passivity, like a hermit relentlessly gauging the right distance from society. In 2008, when I was working on a project around the figure of Robinson Crusoe, who is Oblomov’s exact opposite; I went from the ghostly melancholic type to an earthly and solar being, whose existence was based on requirements of productivity and efficiency.

It is between these two tutelary figures—a very horizontal one and another so diabolically vertical—that I placed Charlie Jeffery and every one of his moves; between stark sterility ‘do nothing, do nothing, do nothing… please don’t do anything, don’t do anything, don’t be anything/ something…’ and creative power ‘I love the universe, I love the moon, I love gravity, I love waves, I love distance and discontinuity…’

Since the very beginning, Jeffery was for me a representation of the male artist, from my generation, with a non-dominant natural inclination, unstable, and sometimes even hysterical. His writings underline and reveal his role as a poet and clearly identify him as an individual who does not hide any of the daily questions and problems that torment him. Jeffery’s short forms are troubling confessions, for example, ‘my body is an organ of fear’ and ‘I’m extremely nervous about existence’. Anyone who would rather reflect upon himself than doze off into normality knows how good it is to be personal, to be open and bilious when it comes to creating something that will not go unnoticed, especially if it skillfully refers to a crude reality; one not yet distorted by large-scale distribution.

Our society is afraid of exposed and exerted feelings. It is generally considered more acceptable to be ambitious and to act rather than to show the signs of being someone who prefers to let his hands dangle in favor of observation. What is inappropriate is not saying that one has a rich inner life (and that you use it to create) but defeating the very essence of creation by making the thought process invisible, like an underground noise or vagabond water that bears no name and that can spring up at any time.

When Charlie Jeffery sings the texts he has written himself, he does it like a true showman, galvanizing his audience with an energy that is all the more effusive that it seems to have slumbered before finding the right time to escape. Charlie Jeffery’s hysteria fills an imaginary void that cannot be ignored. His incredibly secret and intimate oeuvre imposes itself through images at once sensual and profound. His installations are a reference to the powerful world of capital and the aphorisms applied onto shattered and worn out materials, victims of the gravitational force, which are like tranquil grimaces that our bodies make up, unbeknownst to our minds. The emotional excess that Charlie Jeffery uses is a strategy that allows him to avoid looking at things in a partial way, claiming a plural body as the center of a thousand contradictions. The spaces invested by the artist depict the life of a consumer who is ready to differentiate everything. Charlie Jeffery pays attention to sequences that materialize the path of a body that is gendered, genuine, not objectified nor idealized. Form is doubt. Doubt is the possibility of an encounter, the language of an unavoidable physical presence that needs to rub beyond the language of action; a collective Eros that could make us understand how sacred life is.

Cécilia Becanovic