Color Photographs. Early Works (1974-1979)

| Gallery

Tim Maul

Color Photographs. Early Works (1974-1979)

Tim Maul

C-print, 2 images

Image: 9 1/4 x 14 in

Edition of 3 ex

Photo : Aurélien Mole

Courtesy galerie Florence Loewy

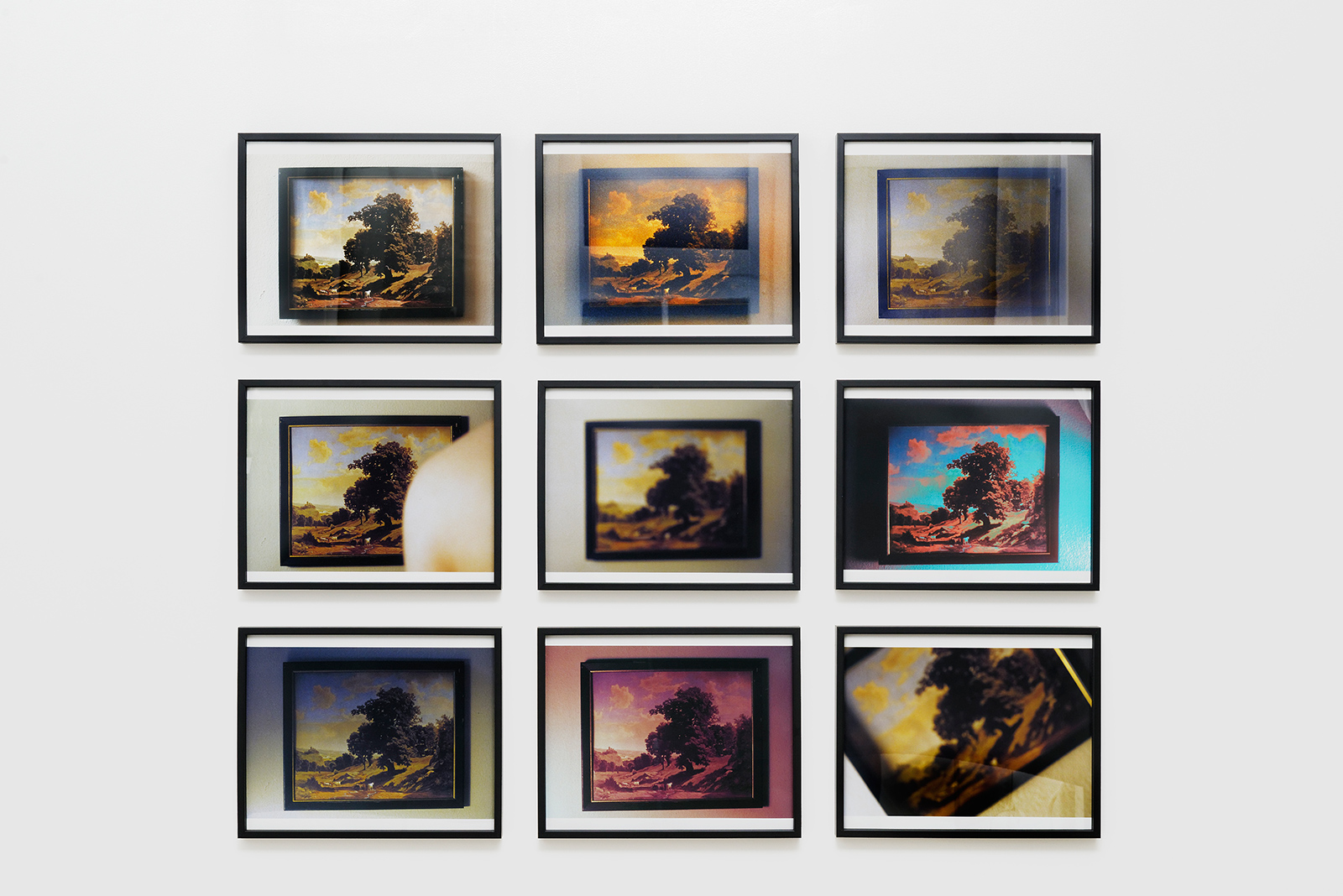

C-print, 9 images

Image: 9 1/4 x 14 in

Edition of 3 ex

Photo : Aurélien Mole

Courtesy galerie Florence Loewy

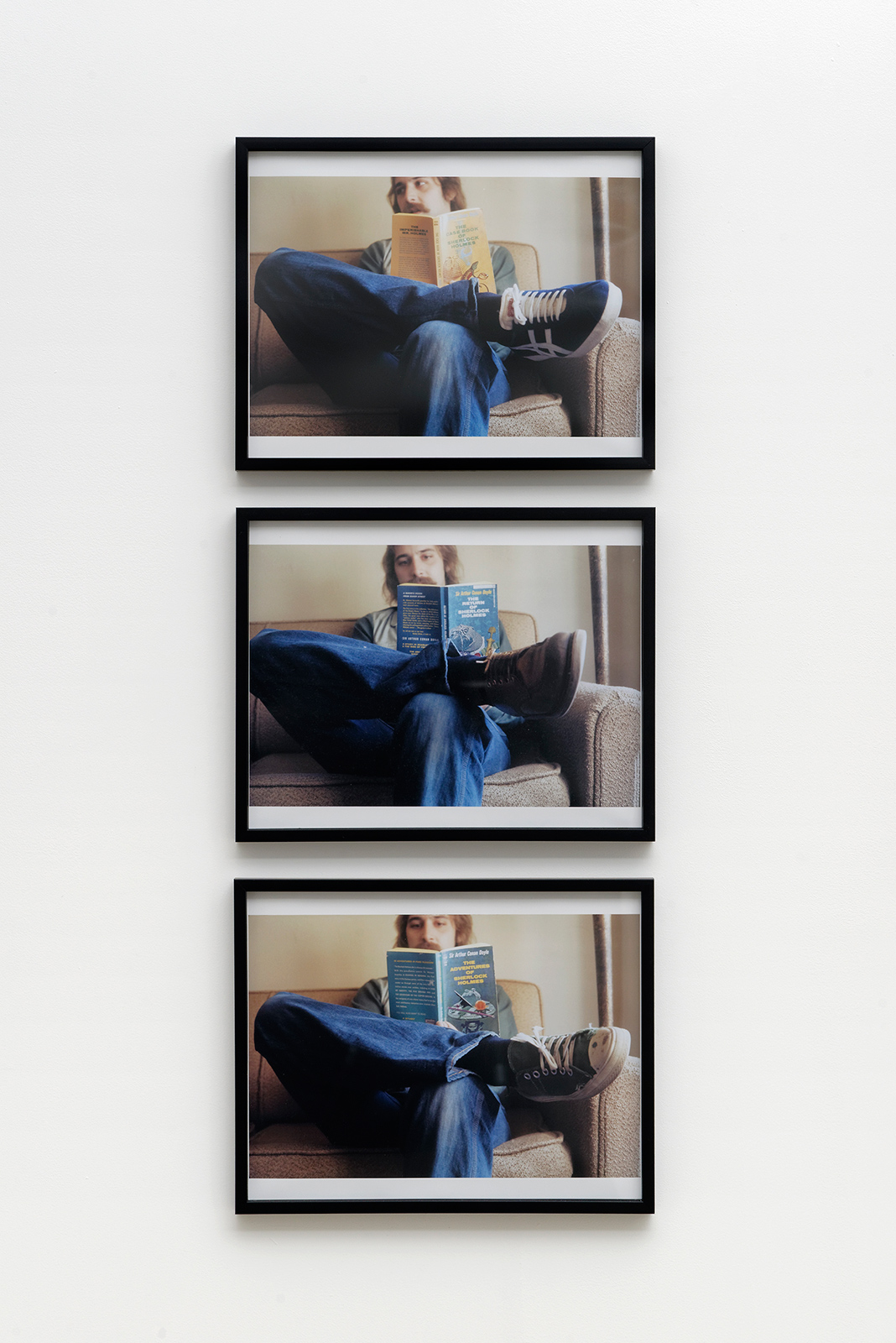

C-print, 3 images

Image: 9 1/4 x 14 in

Edition of 3 ex

C-print, 2 images

Image: 9 1/4 x 14 in

Edition of 3 ex

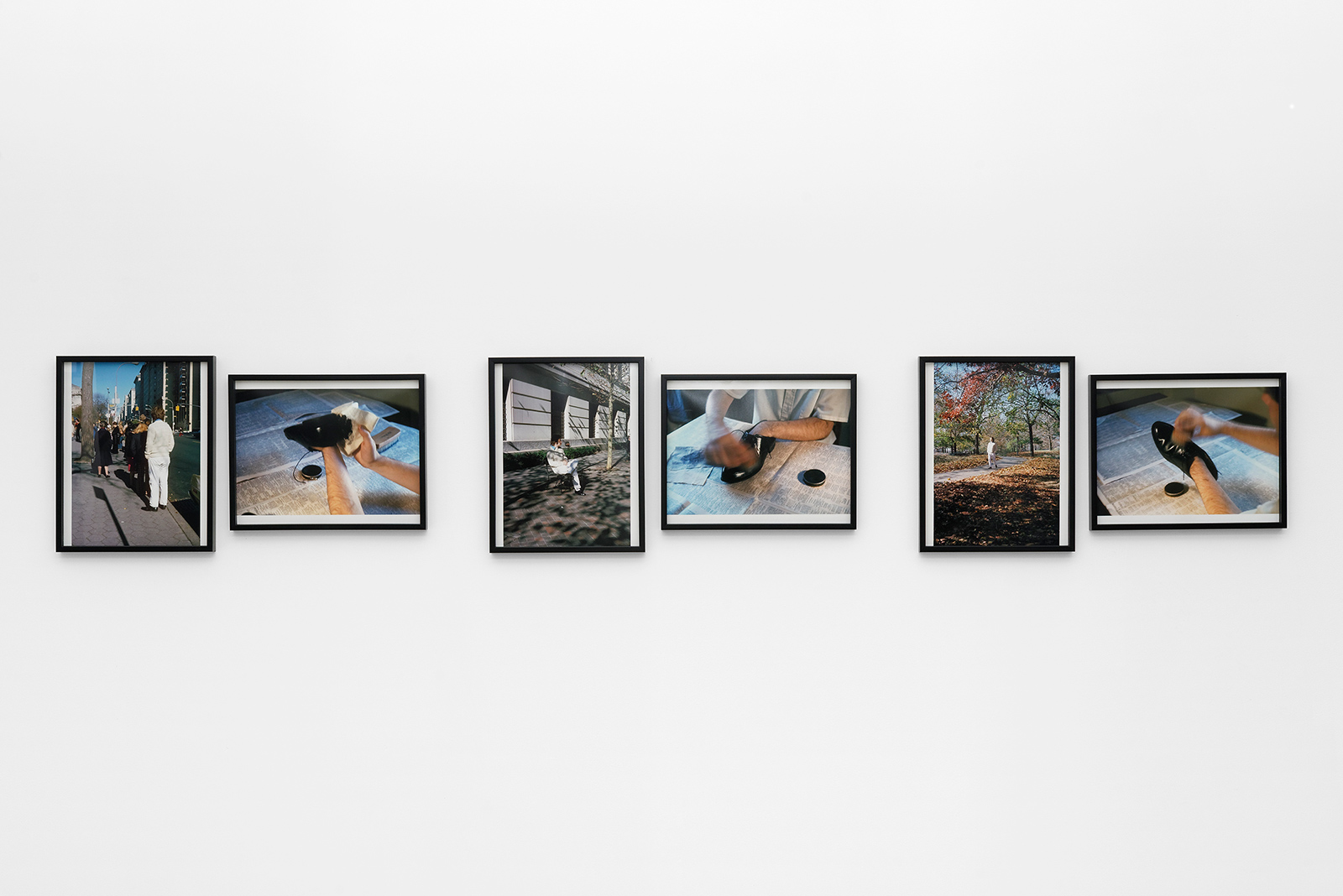

C-print, 6 images

Image: 9 1/4 x 14 in

Edition of 3 ex

C-Prints, 12 images

Edition of 3 ex

EN

The exhibition Color Photographs (1974-1979), Early Works reveals for the fist time a selection of youthful works by the American artist Tim Maul, born in 1951 in Connecticut. These unpublished works, taken from a large group of negatives kept in his archives, shed new light on his photographic production in a career that has been divided, since the 1980s, between an artistic practice, an activity as an art critic, and teaching photography and film at the New York School of Visual Arts.

When he graduated from this school in 1973, Tim Maul decided to abandon painting, in which he had been trained, to turn to photography, a simple, rapid and inexpensive medium in order to work outside the studio, document actions and transmit an idea. He immediately followed conceptual artists who used the photographic instrument as a privileged vector of their experimentations. This can be seen in his first color project, Slides (1973), a systematic registration using a rudimentary apparatus made of 10 sliding boards found in his childhood environment, which pays tribute as much to the typological spirit of the Bechers, the collections of Ed Ruscha, as to Robert Smithson’s A Tour of the Monuments of Passaic, New Jersey in 1967. Not included, this inaugural work, initially designed as a slide projection, was next used in the form of a diptych, which entered the Metropolitan Museum’s collections, determined the principle of the next works made with better equipment: the sequencing of modest images, based on precise rules to be followed, and creating elliptical micro-narratives. These “visual fictions,” as the artist calls them, consequently link a reflective approach to the image production mode with the theme of narration in photography; a protocol that has presided over his creation’s developments ever since.

Without any great technical or aesthetic quality, the photographic pieces of Tim Maul’s beginnings deliberately cultivated ambiguity as to their documentary status. They correspond to two types of projects: some are series of slides, shown at the period to rare contacts, which are akin to free exercise as if to relieve boredom, others are prints produced for applications with a view to continuing his artistic training. Pushed by material need to give up this option, Tim Maul quickly interrupted this solitary experience in Connecticut and moved to New York. There he had a serious of minor jobs as assistant under the patronage of figures such as the French artist Jean Dupuy, the MoMA curator Kynaston McShine or one of the protagonists of Narrative Art, Bill Beckley, who played the role of his mentor. During these bohemian years, when he wasn’t a museum guard or wasn’t working for fashion or a rock magazine, Tim Maul fed his curiosity by reading magazines and theoretical publications (Sunsan Sontag, Ludwig Wittgenstein…). He was equally passionate about performance, Arte povera and artist publications, and remained marked by the repetitive structure of Michael Snow and John Baldessari’s proposals. Far from being anecdotal, these biographical elements and various discoveries were the ferment of his own works in gestation. For these works, Tim Maul made use of ordinary facts of his personal life, daily gestures and objects, which intervened in stripped-down stagings, most often in the neutral décor of his West Village apartment. “I am primarily interested in the relationships that develop between a person and the objects that constantly surround them, particularly in a restricted space, ” he wrote in a 1979 text.

Autobiographical content can best be glimpsed in Shoe Shine (1974), in which Tim Maul replayed, himself, the gesture of polishing his shoes and the route that led him, in his Sunday clothes, to his job as guard at the MoMA. The covers of crime novels that occupied his time while he was on the job are found in the triptych Conan Doyle Project (1974), for which a friend lent him the pause this time. The recurring relationship between interior and exterior space was established in Grand Central Countertop (1974) through the confrontation of a photograph taken in the hall of a New York train station and the recreation of memory, executed when he returned home with the objects that he came across. Other interventions into nature include a procession of hockey pucks arranged among rounded stones (Puck), there a piece of wood hung on a tree trunk like a perch (Perch). In Silver Spoon/Outgoing Tide (1974), the spoon is a symbolic image of privilege that ended up in the sand, which implicitly refers to the expression “to be born with a silver spoon in your mouth.”

The evocative power of trivial gestures and ordinary objects was further strengthened by doubling, the result of the camera seizing two moments of action, a before and an after, which institutes a suspended narrative. These sorts of small performances without a public could consist, for example, in breaking a pencil with one’s hand (Pencil Break, 1979) or capturing the fall of an ash from a burning cigarette (Ash Fall, 1974). If they suggest a certain state of idleness, the artist’s intention was elsewhere. It was clearly a matter, through the radical simplicity of these approaches, with very literal efficacy, to push the spectator to question himself on the perception mechanism itself. With this group of temporal fragments to interpret, Tim Maul stressed both the limits of the photographic tool’s properties and the relationship to the real induced by the image, as though to make us doubt what we see. Likewise, doesn’t the comic motivation present in a good number of these works, which bring to mind the facetious playlets by William Wegman, Robert Cumming and Ger van Elk, simply convey a satire of the art world or a self-analysis of the creative process on the part of a young artist? The treatment of trivial subjects aims in reality at developing a didactic structure, able to concisely raise subtle questions on the nature of the photographic view.

Other arrangements of multiple images in filmstrips, which show the exhaustion of a system through repetitions or successive variations correspond to these short temporal loops. Like a magic trick, the sequence of Two Arrangements (1974) unfolds, image by image, a series of permutations of playing cards and colored flowers in a vase, the whole set down on a red cloth. This principle recalls that of a video by Bas Jan Ader of the same year, Primary Time, that is based on the arrangement of a bouquet in a constantly renewed composition. The attention paid to light effects also enlivens the strange and nostalgic atmosphere of the series of images Sixteenth Street Pastoral (1978), born from the intimate ritual Tim Maul re-photographing an old print from his bed. The reiteration here stresses camera setting errors, as if to signal the next stop of this photo-conceptual research in color. Obtaining, in 1979, his first solo exhibitions in New York and Milan, the artist closed this research phase and soon after started to collaborate with the magazine Flash Art.

Tim Maul’s photographs of the 1970s position him in between generations, between his conceptual elders and the youngest actors of the Pictures Generation. This retrospective glance cast on his beginnings offers in the end a meditation on time, in which time lived and photographic time come together. It is in the merger of these two phenomena that the dimension always as mysterious in his eyes of his preferred medium, whose narrative properties he continues to probe, resides.

As a complement to the exhibition, Tim Maul is presenting, after “Looks Matter” in 2012, a new selection of publications designed as a subjective account of the affinities that his works of the period have with the books of other artists, from Jean Le Gac to Peter Hutchinson, from Robert Filliou to Richard Nonas, by way of Vito Acconci and Robert Barry.

Alexandre Quoi