When in doubt #2

| Gallery

Joan Ayrton, Katinka Bock, Léa Bouton, Hanako Murakami, Amanda Riffo

When in doubt #2

Joan Ayrton, Katinka Bock, Léa Bouton, Hanako Murakami, Amanda Riffo

When in doubt #2

Joan Ayrton, Katinka Bock, Léa Bouton, Hanako Murakami, Amanda Riffo

Exhibition viewFR

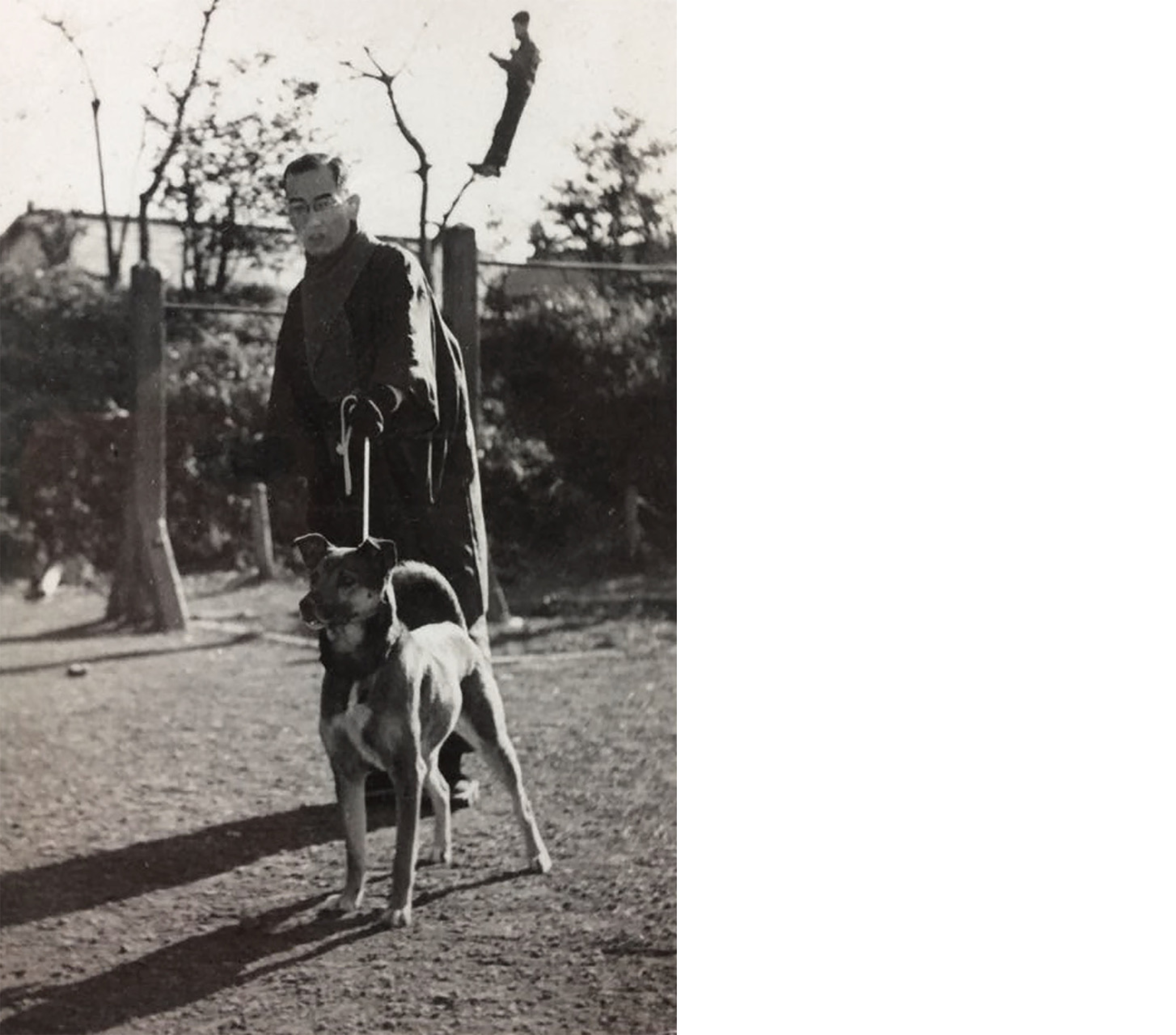

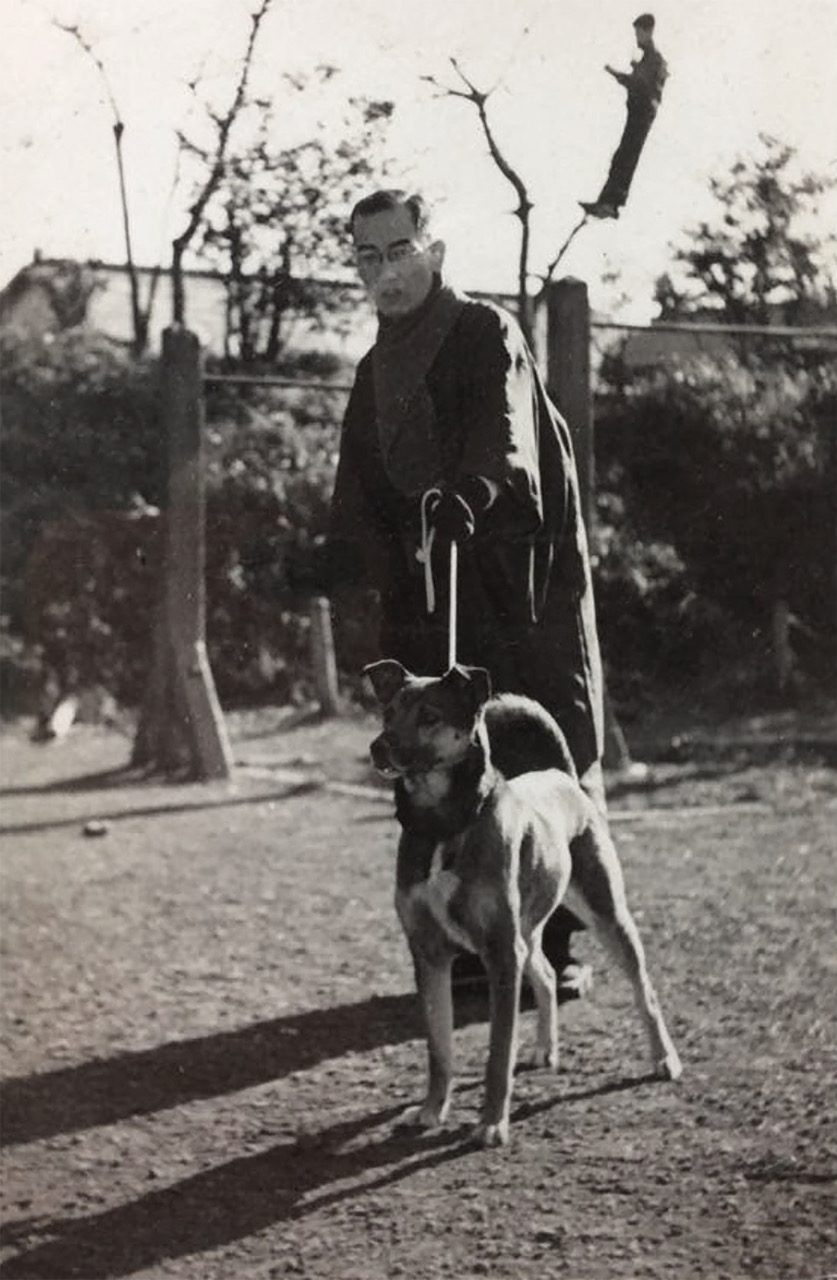

Seichi-san, le père adoptif d’Ikeda Hiroshi, pose avec son chien Kacha, dans la lueur d’un soleil d’hiver, un jour des années d’après-guerre, dans un parc de Tokyo dans le quartier de Shinagawa. Cette photographie est depuis plusieurs décennies posée sur l’autel familial, en compagnie d’autres défunts, humains et chiens. Hiroshi s'incline tous les matins devant cette image, la regarde, allume un bâton d’encens, lui parle, se recueille. Lorsque son gendre Yoann Moreau, physicien et anthropologue français, l’a vue pour la première fois, son regard s’est arrêté sur la silhouette en haut à droite dans l’arrière-plan, légèrement à contre-jour, suspendue dans les airs. Qui était-ce ? Que s’était-il passé là ? Hiroshi et sa fille se penchèrent sur l’image, ni lui ni elle, ni personne dans la famille n’avait jamais vu cette figure dans le ciel.

Yoann Moreau m’a montré cette photographie durant ma courte visite à Izu en 2023, dans le café dont lui et Natsuko, sa compagne, s’occupent une partie du temps. Parti au Japon pour l’École des Mines, et une étude sur ‘l’après’ Fukushima, Yoann s’est vu contraint de changer ses plans suite à l’apparition du Covid, il resta sur place, s’établit sur la péninsule. J’avais montré à Yoann une photographie faite en 2019 lors d’un premier séjour au Japon. Une femme vêtue d’un kimono, marchant devant moi dans une ruelle de Tokyo, coupée en deux par mon Iphone : un glitch, une fissure, un accident d’image. Cette photographie m’a hantée. J’y ai mis tout le poids de la catastrophe intime. Mais aussi de celle, collective, d’un monde qui chaque jour se dérègle davantage. Yoann répondait à une image par une autre, j’étais sidérée par l’étrangeté de la silhouette suspendue, demeurée invisible aux yeux de la famille. Était-ce la part affective qui opérait, l’émotion ne pouvant se trouver en deux endroits de l’image ? Or la silhouette une fois vue, me dit Yoann, suscita peu de questions. Le grand père et Kacha étaient ce qu’il fallait voir.

On porte en soi les visions, les fragments de vies vécues par d’autres avant nous. Ma mère m’a récemment raconté qu’une étrange fine lueur blanche planait à l’horizon, au-dessus du Japon, le 6 août 1945, visible depuis Shanghai où elle a grandi durant la guerre. Cette vision n’est pas la sienne, elle l’a eue des yeux d’un autre ; elle est encore moins mienne, mais les images voyagent en nous, le plus souvent à notre insu, et affleurent parfois, comme le limon du fond d’un lac, donnant sens à nos obsessions souvent inexpliquées. Mais sait-on voir ‘ce qui arrive’ ? Y parvient-on vraiment ? Yoann me raconte le souvenir d’une survivante de Fukushima qui, dans le temps court qui sépara le tremblement de terre du tsunami, eut la vision terrifiante, depuis la falaise ou elle vivait, du retrait de l’océan, de sa disparition complète. Nous nous demandions, dans notre échange, comment voir ce qui n’a jamais été vu, comment appréhender une vision sans précédent.

Étrange et fabuleuse aventure que celle du regard moderne, des technologies qui depuis les premières chimies de la photographie argentique repoussent les frontières de l’invisibilité. Plus grand-chose ne résiste à la capture en image, le monde est désormais, jusque dans ses dimensions extrêmes – phénoménalement petites ou phénoménalement grandes - à disposition du regard, saisissable à l’envi (me vient à l’esprit la photo de Harold Edgerten, sidérante, de la fission d’un atome en 1952). Et c’est tout le régime des images qui a basculé le jour où, grâce à (ou en dépit de) la radioactivité, on inventait le rayon X. Voir au travers de la matière a ouvert les consciences et les imaginaires sur une réalité plus complexe que celle que les yeux percevaient, sur un espace intérieur, devenu espace de rêves, d’explorations occultes, de visions hallucinées.

Le monde désormais si visible défile furieusement – les mêmes images vues partout 1 fois, 3 fois, 10 fois, mille fois, mille fines lueurs blanches au creux de nos mains ; nos lexiques s’enrichissent au gré de nos états de consciences épuisés – fatigue informationnelle, doom scrolling … Plus que jamais, et même ces jours où se dessine sous nos yeux un nouveau monde devenu fou, je pense aux psychés (la mienne du moins) prises au piège, endormies, enlisées malgré la stupeur et l’angoisse. Et puis il y a la rencontre d’une image qui parmi toutes m’arrête, un jour de printemps au Japon. Son mystère, sa prégnance, un récit. Ce qui n’a pas été vu, ce que Yoann m’en a dit. Je reste avec l’étonnement de nos visions sélectives, de ce que – par amour ou par effroi, ou par quelque autre affect – on manque de voir. Quelque chose d’important a lieu dans ces glitchs, ces ratés, dans le doute. L’exigence d’une attention, un ralentissement. Ce sont je crois dans ces failles que se forment tranquillement des communautés de regards.

Je remercie Hiroshi, Yoann et Natsuko, de m’avoir prêté la photographie - et Léa, Katinka, Hanako et Amanda de se prêter au jeu de l’exposition, du croisement des images, des visions et fixations chimiques.

Joan Ayrton

***

EN

Seichi-san, Ikeda Hiroshi's adoptive father, poses with his dog Kacha, in the glow of a winter sun, one day in the post-war years, in a park in Tokyo's Shinagawa district. This photograph has been placed on the family altar for several decades, along with other deceased humans and dogs. Every morning, Hiroshi bows to the image, looks at it, lights a stick of incense, talks to it and meditates. When his son-in-law Yoann Moreau, a French physicist and anthropologist, saw it for the first time, his gaze fell on the silhouette in the top right-hand corner of the background, slightly against the light, suspended in mid-air. Who was it? What had happened there? Hiroshi and his daughter looked at the image; neither he nor she, nor anyone else in the family had ever seen the figure in the sky.

Yoann Moreau showed me this photograph during my short visit to Izu in 2023, in the café that he and Natsuko, his partner, run part of the time. Yoann had gone to Japan to carry out a study commissioned by the École des Mines on the after-effects of Fukushima, but was forced to change his plans when Covid appeared, he stayed behind, settled on the peninsula. I had showed Yoann a photograph taken in 2019 during a first visit to Japan. A woman dressed in a kimono, walking in ahead of me in a small street in Tokyo, cut in two by my iPhone: a glitch, a crack, an image accident. The photograph haunted me. I put into it all the weight of an intimate catastrophe. But also the collective catastrophe of a world more and more out of control. Yoann responded to one image with another, and I was stunned by the strangeness of the suspended figure, invisible to the family. Was it the emotional part operating from within, as emotions can’t occur in two places of an image? But the silhouette once seen, Yoann tells me, raised few questions. The grandfather and Kacha were what had to be seen.

We carry within us the visions, the fragments of lives lived by others before us. My mother recently told me that on August 6th 1945 there was a strange white glow on the horizon over Japan, visible from Shanghai, where she grew up during the war. This vision is not hers, she had it from someone else's eyes; it is even less mine, but images travel within us, most often without us knowing, and sometimes surface, like silt from the bottom of a lake, giving meaning to our often unexplained obsessions. But can we see ‘what's happening’? Do we really? Yoann tells me about a survivor of Fukushima who, in the short time between the earthquake and the tsunami, had the terrifying vision, from the cliff where she lived, of the ocean receding and disappearing completely. We wondered, in our conversation, how to see what has never been seen before, how to grasp an unprecedented vision.

It's a strange and fabulous adventure, the one of the modern eye, of technologies that have been pushing back the frontiers of invisibility since the first chemistries of silver photography. The world, even in its extreme dimensions - phenomenally small or phenomenally large - is now available to the eye, and can be captured at will (Harold Edgerten's mind-blowing photo of the splitting of an atom in 1952 springs to mind). And the whole system of images was turned on its head the day that, thanks to (or in spite of) radioactivity, the X-ray was invented. Seeing through matter opened people's minds and imaginations to a reality more complex than that which the eyes perceived, to an inner space become a place of dreams, occult explorations and hallucinated visions.

The world now so visible scrolls furiously by - the same images seen everywhere once, 3 times, 10 times, a thousand times, a thousand fine white glows in the palm of our hands; our lexicons are enriched by our exhausted states of consciousness - information fatigue, doom scrolling... More than ever, and even these days when a new world gone mad is taking shape before our eyes, I think of the psyches (mine at least) trapped, num, stuck despite the stupor and anguish. And then there is the encounter with an image that stops me in my tracks, one spring day in Japan. Its mystery, its force, its story. What was not seen, what Yoann revealed. I'm left with the astonishment of our selective visions, of what - out of love or fear, or some other affect - we fail to see. There is something important in these glitches, these failures, in doubt. A demand for attention, for a slower pace. I believe it is in these cracks that communities of vision are quietly formed.

Many thanks to Hiroshi, Yoann and Natsuko for lending me their photograph – and to Léa, Katinka, Hanako and Amanda for playing along with the exhibition, crossing images, visions and chemical fixations.

Joan Ayrton

- Joan Ayrton

- Katinka Bock

- Léa Bouton

- Hanako Murakami

- Amanda Riffo