Slow Melody Time Old

| Gallery

Joan Ayrton

Slow Melody Time Old

Joan Ayrton

Slow Melody Time Old

Joan Ayrton

Exhibition view

Slow Melody Time Old

Joan Ayrton

Exhibition view

Slow Melody Time Old

Joan Ayrton

Exhibition view

Slow Melody Time Old

Joan Ayrton

Exhibition view

Impression sur papier

Edition of 3 ex + 1 EA

2016, vidéo HD, son, durée 7:30, studio GetSound, Villa Savoye - Le Corbusier

Edition of 3 ex + 1 EA

©FLC-ADAGP

Florence Loewy & Théophile

Paris, offset noir et blanc, non relié, sous blister, graphisme : Alex Chavot

EN

Slow Melody Time Old

“This phenomenon can be compared to a ‘transfer’ from the artist to the spectator in the form of an aesthetic osmosis that takes place through inert matter: color, piano, marble, etc.”

Marcel Duchamp, Le Processus créatif[1]

Gray filters on the windows. A dark gray, unrolling its film-color in a Cinerama, and whose amber becomes deep green inside the Florence Loewy gallery. It is the magic of gray, which however is not neutral…

Nevertheless, how can we not think about it? Neutral gray, which enables the calibration of colors in photography, the uniform division of ink in printing – that gray the perception of which varies according to what is nearby. The gray of tuning, chords.

The gray becoming that “suspension of conflicting data from the discourse,” to quote the argument of Roland Barthes’ celebrated course on the neutral at the Collège de France.[2] Better still: the gray becoming that “inflection that eludes or thwarts the oppositional paradigmatic structure of meaning.”

The strange fir gray plunges the exhibition space into a half-light favorable to the projection of the film Searching for an A – a story of tuning, instrument and temperance, to be exact. Installed in the main salon of Le Corbusier’s Villa Savoie in Poissy, a baroque string quartet[3] plays a piece composed, by means of slide show with sound, by the artist Joan Ayrton herself. A piece that music-lovers know well and that, on the cusp of each concert, generates that twinge full of promises. Tuning. Sounds, then notes. And other sounds. A melody that will not be written – whose onlookers (listeners) will not hear any crevices. The four musicians tune, indefinitely; indefinitely, their instruments, whose strings are in catgut, are out of tune. The familiar twinge, both joyous and worried, is prolonged, it too, indefinitely. The promises remained suspended through the long black screens, tracking shots rolling out Le Corbusier’s architecture, shots on the absorbed faces, hands that are searching for the A.

A choreography with introductory gestures and rare images is gradually written. It speaks of the uncertain quest for an understanding; the many attempts, to patiently correct the natural aberrations – acoustic in this case. But not solely. All our aberrations. To attempt to maintain a few well-tempered instruments in the social relationship (among others). Moreover, Joan Ayrton recounts that this film was born in 2013, during a study trip that led her, among other places, to Tijuana, sadly famous for its maquiladoras.[4] She met Mago there, a union activist, in a closed and deserted shopping center; there, thousands of kilometers from her home, the artist suddenly heard “those few notes recognizable among all others, the fifths of a violin that is tuned to the diapason.” It was the shock, specific to any telescoping of realities that we believed were far from us: “They are two voices that that day bore the idea of universality, that of Mago through his history and his fight against social justice, that of the mysterious musician, bent over her violin, searching for the A.”[5]

To get in tune, a standard must be established: a frequency for the A (whose story in the text previously cited Joan Ayrton recalls,), a standard for architecture (Le Corbusier’s Modulor being only one example among others). Everything is a question of measure, of moderation, once again. That of profoundly human efforts, presented here; nothing of hubris – of labor and humility. That of their décor: a house thought of for use but that the site’s visitors know has suffered from the passage of time, as well as many creations of the illustrious Charles-Edouard Jeanneret-Gris. In which the universalist utopia would almost appear as an obsolete functionalism…

However, paradoxically, there no longer seems to be any measure, moderation in Searching for an A. There is nothing but circularity. The camera literally goes around the owner, in sync with this architectural score the ribbon of whose windows stretches 360°: infinities carried in a loop, like the film itself. Universalism no longer sufficing, the cosmogonic takes over. Something escapes, in fact. Would it be the “Pythagorean comma,” that natural and mathematical aberration that Joan Ayrton defines as “a little too much void, a small surplus of space (infra-mince) that the musician must divide in a relatively equal way between the notes of the scale”[6]? The extreme dilation of durations and the incessant resumption of the exercise snatches the eyes (and the ears) from its condition. A plunge is taken into this infra-mince that the artist points to: a massive zoom into this remainder of space-time that, in so doing, becomes in its turn infinitely vast and swarming with all the durations that the eye alone does not perceive.

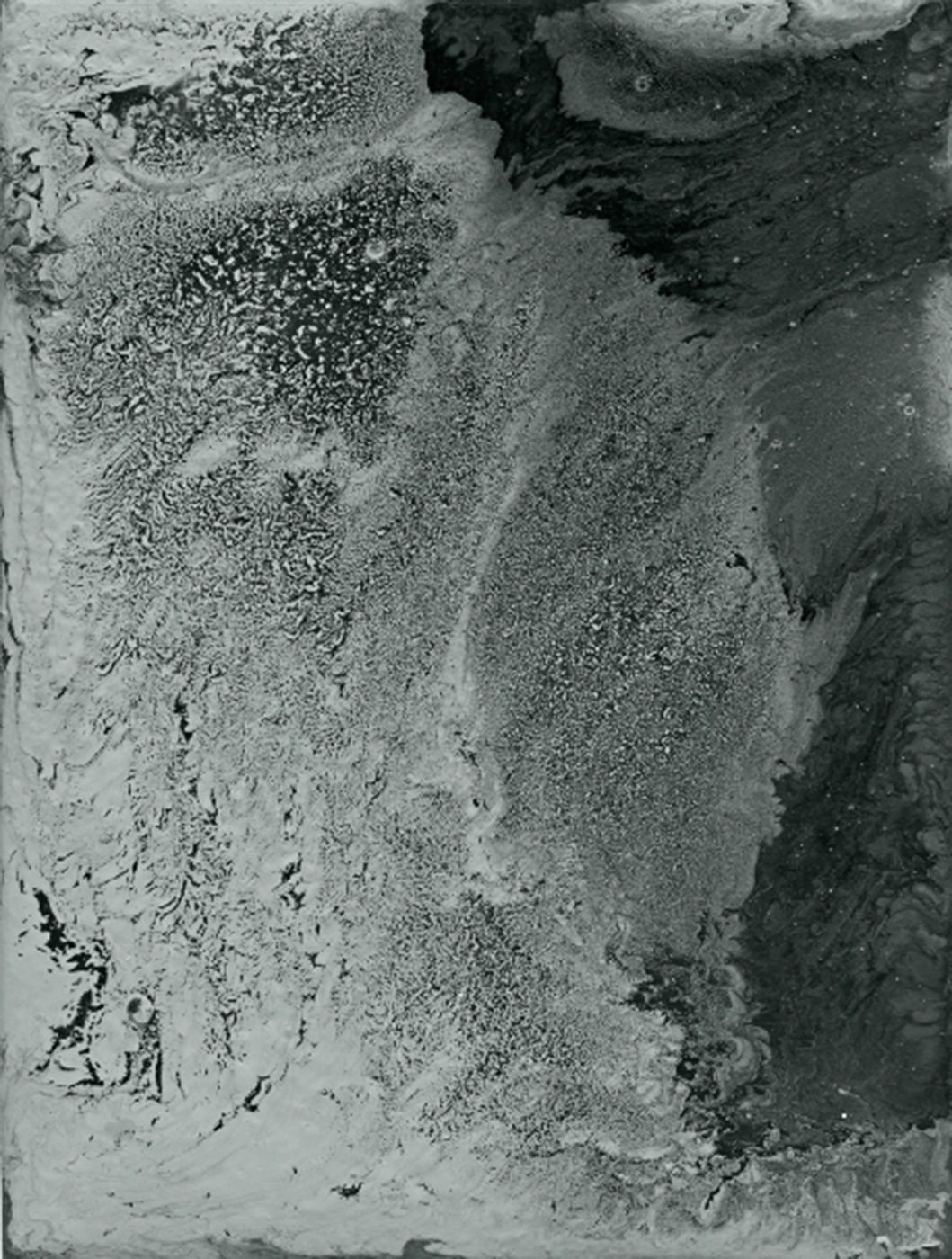

Because the magnifying glass through which Joan Ayrton examines matter does not only reveal its physical composition, it makes the slowest and most imperceptible changes in state visible. The inert shakes itself, becomes animated – it flows, cuts across, changes direction, occasionally coils upon itself. We witness, with the impression of being present at a live performance, a geological event. I hear gentle cracking, dripping, then streaming. Thus of Flow, produced for the exhibition. This printing on paper is part of the continuity of the artist’s search; she redeploys through black and white photography small (very small: mostly 9 x 12 cm) glycerophtalic lacquer paintings on metal. Painting-matrixes that contain the universe in a reduced form, supports for the most poetic and unlikely daydreams, in the style of Roger Caillois. “The possible implying the becoming – the shift from one to the other occurs in the infra-mince.”[7] And here we are. The shift: that of color that cuts a path in a fluid motion that evokes the ancestral techniques of mottling on paper, whether it is Italian, Icelandic or Japanese.: On this image, more than usual in Joan Ayrton’s work, we perceive a deposit skimming the surface, water that contains something – but what? Pigment, ore? I keep hearing it, this inert, immemorial something that murmurs: “color, piano, marble, etc.”[8]

“It can happen that this is a sound piece with images,” Joan Ayrton confided to me, during a visit to the studio, concerning the film Searching for an A. And I can’t help thinking that the musical – or at least the sound – thing impregnates all her works. Something of the “rhythm uncreated in the universe.”[9] Flow returns the material to its “attracters,” those geometric figures modeling chaos: in which the internal upheavals are gradually organized, in a wrong-way movement, somewhere, of the harmonic tension trying to repair natural and mathematical aberrations.

Slow Melody Time Old, a small edition also produced for the exhibition (and that gives it its title) comes from the same silent music that the spaces between make sound – between states, the strata of scales, beings. I realize that it is also printed in black and white; I am amazed, but I remember that I often correct (inevitably, I should admit) the colorimetry of Joan Ayrton’s works, when I think about it, after the fact: the black and white works turn into colors in my recollections, and vice versa. Would I repair the aberrations? Or would it happen that we never really know, as when we awaken from dreams, in what chroma they were played. Neutral grays taking on the hue of what is nearby, surely. Or being veiled, as Flow, with a verdigris film – a corrosion of the image that is not really one, obviously.

Slow Melody Time Old came out of the melancholic daydream – a timeless ballad, through a few shots taken in the archeology museum in Athens. The glance, of course. Which lingers, both vague and precise. Like attention, in reality. We grasp it, elsewhere, already, hanging on the tree-lined surroundings of an antiquated exoticism, then, lingering on a step, a junction between different soil qualities, earth, stone, movements whose mineral fluidity – although frozen – evoke Flow. It lingers on architectural details, and on the marble bases that, photographed in this way, once again become, potentially, papers found during another of the artist’s trips, small paintings in glycerophtalic lacquer on metal, other mottling, other places, other periods. These bases seem to be steles, although the images only retain their contemplation, and the fragility of the bodies, present everywhere, astonishingly, in this edition as in the projected film.

The glance envelops the sculptures with their timeless postures – in a disturbing, moving fashion: a young girl shivering, a garment like bikini bottoms. It frames the wall notes, the objects exhibited in the windows. Figurines in the form of violins. Searching for an A resonates around me, in the Florence Loewy gallery, but perhaps in Athens still. It resonates with many references to art history, and in particular to modern art in which violins and company were a recurring motif (the instrument and the musicians being present in the entire iconography for centuries and centuries). Without forgetting the hand – another persistent iconographic theme, and not the least, notably in Western painting. The hand that plays, that gives: that gives objects as much as it gives form(s). What are the couple on the bas-relief standing out from the black ground exchanging? A glance, bread, attention?

It is a kind of song of gestures. A music of gestures and too many, or too few spaces. Movements that repair the aberrations and create new ones. From the labor of humans, the labor of rocks, sediment and flows.

It is a kind of song of gestures in which minor and major history are recounted. Not that of our lives crisscrossed into the course of things, not exclusively; that of matter “On a grand scale: on a small scale,”[10] comparing the scale of the body to geological periods, that of this Athenian earth on which was built the museum where objects found there are exhibited, at the very spot. Vertigo, confronted by the loop, the cycles.

A story of measure, of moderation and of immoderation. Beating immoderation.

Marie Cantos (August 2017)

[1] Marcel Duchamp, Le Processus créatif (1957), L’Echoppe, coll. “Envois,” collection, Paris, 1987, n.p.

[2] Roland Barthes, Le Neutre. Cours au Collège de France (1977-1978), text established, annotated and presented by Thomas Clerc, Seuil / Imec, “Traces écrites” collection, Paris, 2002.

[3] The Pygmalion ensemble.

[4]Joan Ayrton, “Searching for an A,” in Cahiers du post-diplôme Document et art contemporain, no. 6, October 2013, p. 14-21.

[5] Idem, p. 15.

[6] Idem, p. 18.

[7] Marcel Duchamp, “Infra mince (1-46)” in Notes (1980), Flammarion, “Champs Arts” collection, Paris, 2008, p. 21.

[8] M. Duchamp, Le Processus créatif, ibid., n.p.

[9] Alphonse de Lamartine, “Première préface” in Les Méditations poétiques dans Œuvres, Edition des Souscripteurs. Bd. 1: Méditations poétiques avec commentaires. Paris: Firmin Didot 1849, S. 1-26.

[10] Paul Célan, Partie de neige (1971), translated from the German and annotated by Jean-Pierre Lefebvre, Seuil, “La Librairie du XXIe siècle” collection, Paris, 2007, p. 89.

translated by Eileen Powis