Salto di Tiberio

| Gallery

Florian Bézu

Salto di Tiberio

Florian Bézu

Salto di Tiberio

Florian Bézu

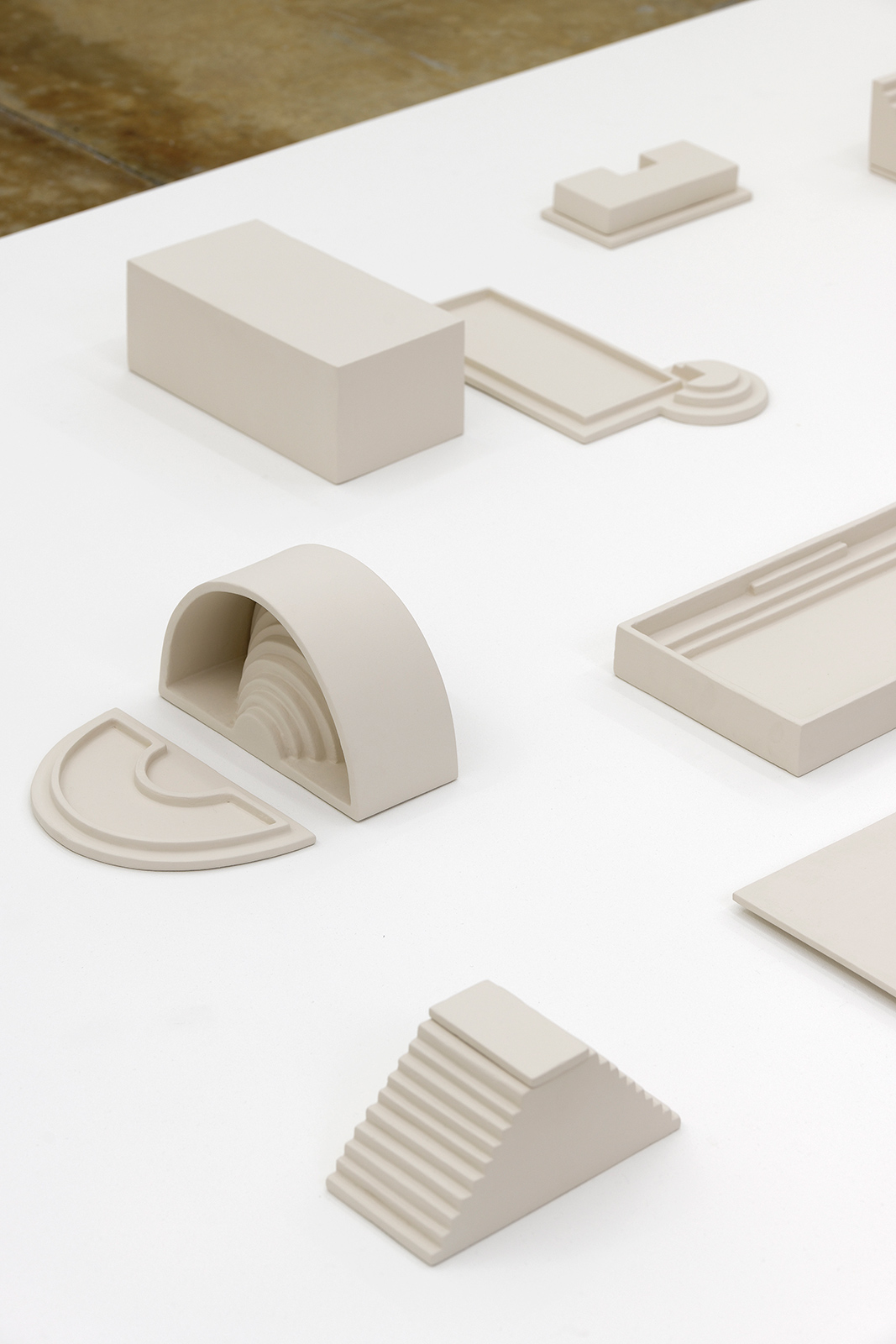

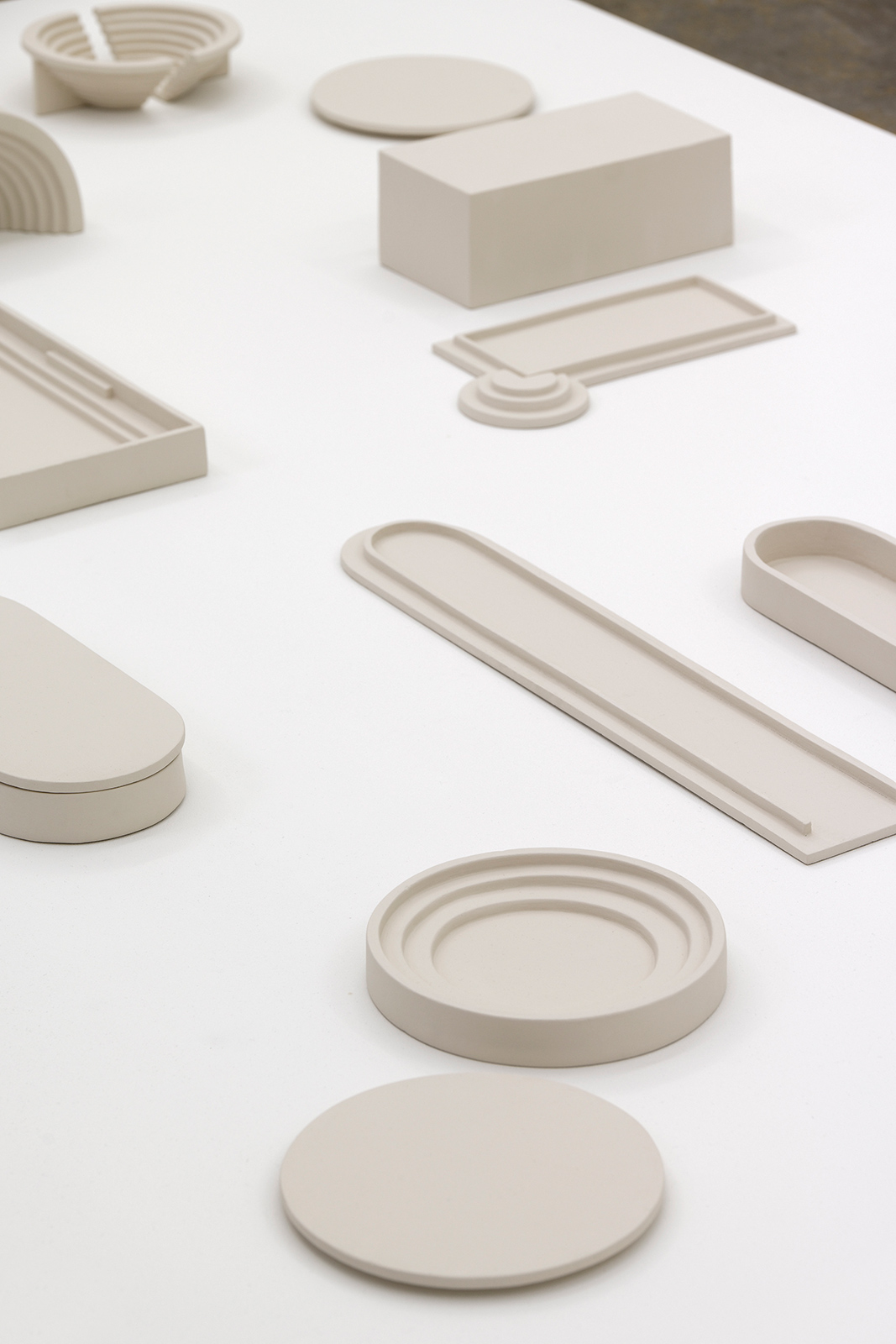

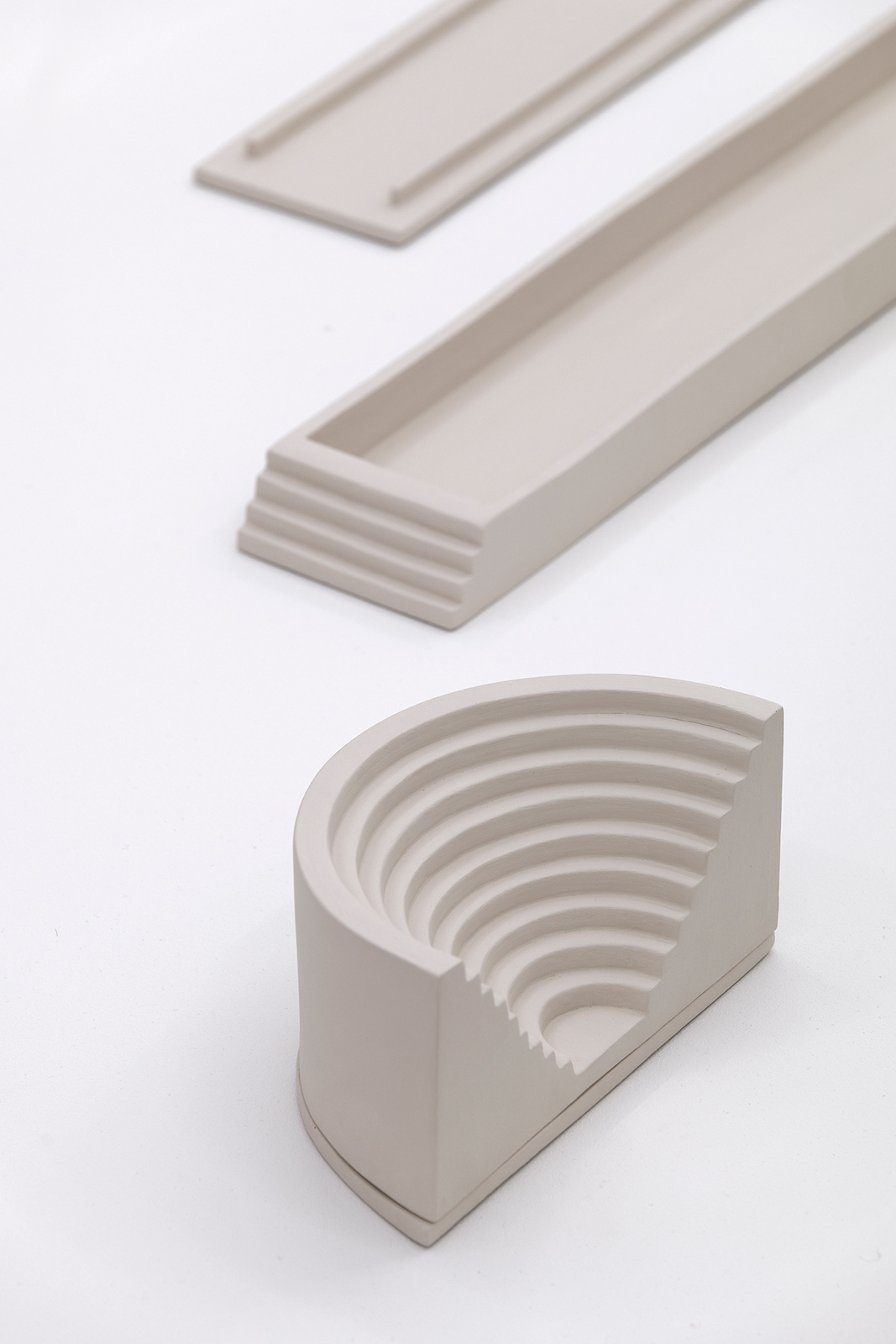

Exhibition view

Salto di Tiberio

Florian Bézu

Exhibition view

Salto di Tiberio

Florian Bézu

Exhibition view

Salto di Tiberio

Florian Bézu

Exhibition view

Salto di Tiberio

Florian Bézu

Exhibition view

Salto di Tiberio

Florian Bézu

Exhibition view

Salto di Tiberio

Florian Bézu

Exhibition view

Salto di Tiberio

Florian Bézu

Exhibition viewText by Sabrina Tarasoff

Dear F.,

Lately I have been having many writing dreams. Most of them involve an un-burdening inversion of the written versus spoken word, a movement into some dream-reality wherein the physical stuff of language just won’t stick to paper or appear on a screen, and so anxiety exalted I wind up reciting to myself, softly yet out-loud, the contents of whatever I am hoping to inscribe. Out of mouth, each word incanted follows a rush of vertigo related to being dropped; like death and its rumored dopamine rush, I feel myself falling with language in a giddy fit of laughter. In the morning, what I’ve committed to memory is not what my oneiric treatise was “about,” but rather the sensation of it—the sensation of writing as it falls off the ledge of thought.

In a dream, right on queue, I move to write about your sculptures, though in this one writing is not what is on ledge—I am. High up on a perch, (ostensibly called “criticism” though let us not go there,) I’m trying to take notes on the mini-polis of polished and painted clay models of Roman architectural forms, dwarfing by my size each one of little monochrome cavea, nymphy grotto, seamy bathhouse and bench-seated gym. My task is clearly ekphrastic, yet since text is still not sticking to paper, speech instead spills out in its unthinking ways. The words are all so densely connected that as they fall their coenesthetic sensibility is simply a big whoosh! The movement sweeps me along, and as I lay falling, I snap awake.

In broad daylight I am searching back to the threshold between writing and speech, speech and your sculptures, …

“This vertigo in its two forms introduces excorporation as well as projection mechanisms. The attracting external void often turns out to be a projection of the patient’s feeling that he has an inner void. He has different ways of feeling anx-ious about, and fascinated by, the external void, depending on what he projects in-to it; moreover, depending on his projections, this attractive outside changes: it may be felt to be an unfathomable external void, but equally well a relational space filled with riches.” (Danielle Quinodoz, Emotional Vertigo: Between Anxie-ty and Pleasure, 1994.)

“And yet they were so brilliant, these paragraphs, so nobly phrased, so lightning-like in their illumination, that the dead seemed to crowd the very room. Read con-tinuously, they produced a sort of vertigo, and set her asking herself in despair what on earth she was to do with them?” (Virginia Woolf, Night and Day, 1920.)

“The world and all the people in it had suddenly slipped beyond her comprehen-sion and she felt in great danger of losing the whole world once and for all–a feel-ing that is difficult to explain.” (Jane Bowles, Two Serious Ladies, 1943.)

… And so on, excavating the giddy feeling of encountering your work point-blank, especially within the schism of dream/no-dream wherein measures such as distance and scale are dizzied. So what of the production of vertigo in your work? It is a confounding experience to go back and forth between each matte, nouvelle sculpture and the blankness of a writing page, especially working within a deftly meandering network of references. The formal ambiguities of those small-scale models of antique forms of yours, inspired by souvenirs often collected by young men of the 18th century off on their grand tours, act apposite to such threshold spaces. Sites for fantasy, projection—my first notes on them read…

So many hiding spots exist within those forms. I want to play in this pleasure ground, paying no heed to how my body exceeds any maximum capacity. Like so, I wish upon myself a case of Alice in Wonderland syndrome, which would allow me to at least experience myself to scale—cram myself into the unoccupied spaces, race around the ‘mini grand prix tour’ and explore the space for its strangeness.

… which is to say, your works push me into an idea of writing as a textual space wholly contingent on the very experience of a looking, listening body. Ekphrastic, but also onomatopoeic and aural, maybe sentient. To clarify, your sculptures do not fall like my language does in dreams. They’re too graceful and too measured. They induce the feeling of falling, caving in, sinking. Staring at tiny toy homes from above, feeling oneself far removed from the world (from history, from aes-thetic principles, from color, sensation, sensationalism?)

I digress. In my dream your sculptures shifted in matte and impervious colors, like mood lighting on airplanes that toy with our perception of time. The whole ‘city’ would transition from a shy, ingenue violet to a sudden pink, a soft shock, right before the mini-polis was blanched, turning pale as though scalded and shocked out of color. No surprise, considering the multiple colors that you con-sidered painting the sculptures, nor thinking to the Salto di Tiberio itself. An es-carpment off the coast of Capri, rumored in history as Emperor Tiberius’ choice location for casting off recalcitrant lovers and misguided guests—I can only imag-ine the face of Tiberius’ victims blushing similarly only to turn drain of color when realizing the leap they’re about to make.

When I woke up from my perch, I was stuck on the sound of the fall. A swoosh, but maybe a gasp, or a blankness seen in the small grooves and tracks of your work, which caught my breath in a similar convulsion somewhere between the pleasure principle and the anxiety it exalts. When I consult the web for what condition could be given to such threshold states, I am given a long list of diag-noses. I might alternately have a Vitamin B deficiency, or suffer from a ‘painful sadness’ more commonly known as depression, the l’heure bleue making a whole room spin, or even be back in a state of puberty, a dizzying thought in itself, or have sleep apnea, anemia, hypothyroidism, or a Bowie-sounding condition known as Labyrinthine, which produces disturbances of balance, a positional ver-tigo, and undesired eye motions. You feel, even with the slightest motion, like you are going to fall, like so…

“For those things, whose unmanageableness, even when represented on paper, makes one gasp with a sort of amused horror, were manned by men who are his direct professional ancestors.” (Joseph Conrad, The Mirror of the Sea.)

“… so vivid, dissociated, self-aware, and flat-out poetic in its description of day-to-day survival and transcendence that it verges on claustrophobic in its realiza-tion of setting, character, and plot. In some places, I had to force myself to look up and away from the words and gasp for air.” (Kate Clinton on Eileen Myles’ Cool For You.)

“Her sentences came in little gasps.” (E. Phillipps Oppenheim, The Malefactor.)

…. a list in literature, which surely goes on forever; to gasp is quite general as it turns out, but no fall without it. Perhaps writing in that space of the “salto,” the leap, the jump, necessitates a push—

I am grateful to be tumbling per your push.

Best,

S.