Sharp-eyed

| Gallery

Caroline Reveillaud

Sharp-eyed

Caroline Reveillaud

Sharp-eyed

Caroline Reveillaud

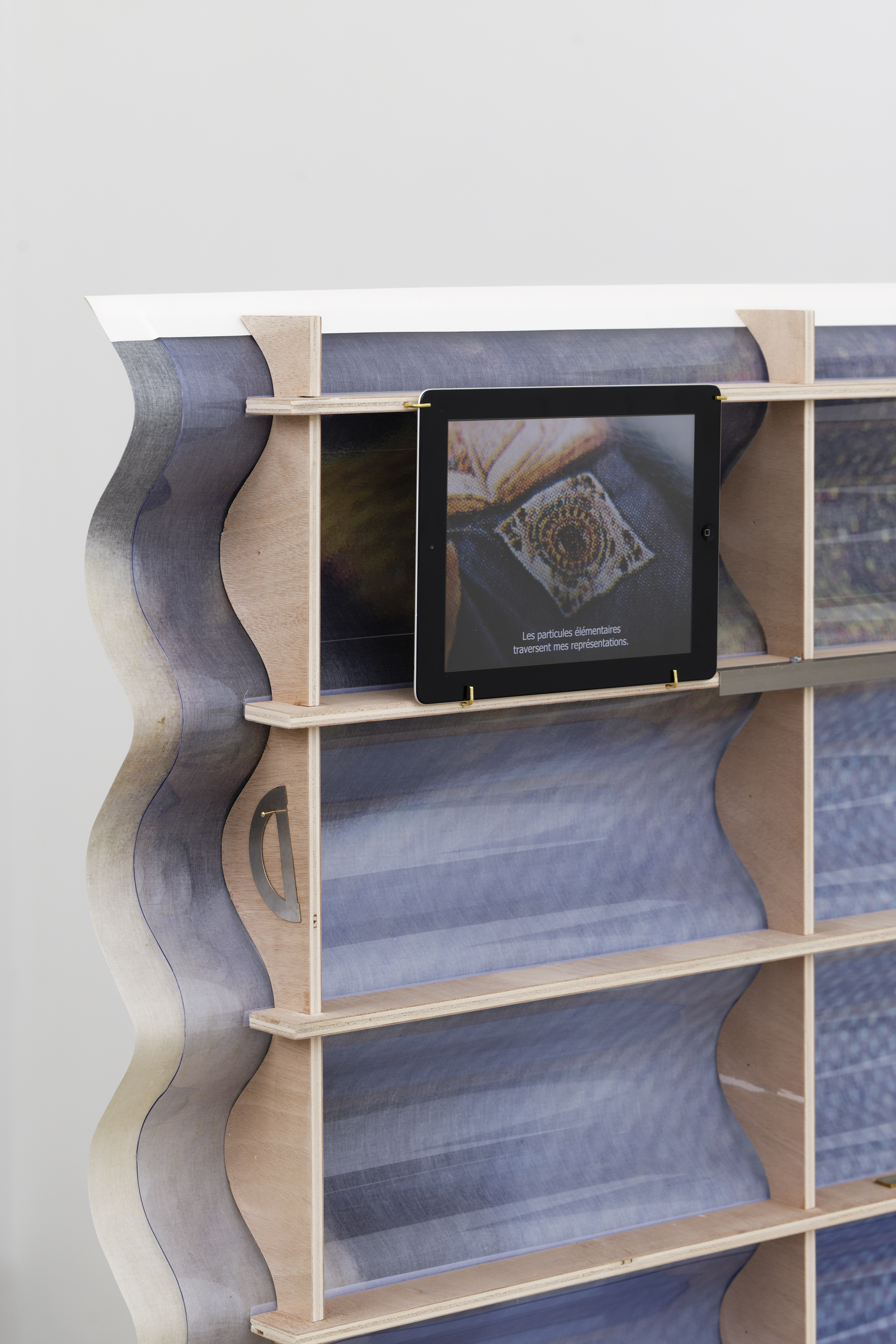

Exhibition view

Sharp-eyed

Caroline Reveillaud

Exhibition view

Sharp-eyed

Caroline Reveillaud

Exhibition view

Sharp-eyed

Caroline Reveillaud

Exhibition view

Sharp-eyed

Caroline Reveillaud

Exhibition view

Sharp-eyed

Caroline Reveillaud

Exhibition view

Sharp-eyed

Caroline Reveillaud

Exhibition view

Sharp-eyed

Caroline Reveillaud

Exhibition view

Sharp-eyed

Caroline Reveillaud

Exhibition view"Glitch" (2022), full video available on this link / password : glitch2022

EN

Eyes wide open

Alexandra Goullier-Lhomme

Seeing, in the extension of its lexical field – eye, sight, visible, vision, visionary, permits us both to create an image of the world that surrounds us, to know it and recognize ourselves, to move easily, to anticipate and predict, to reveal, reason, control, be moved and even believe. In a maze of popular expressions: “seeing is believing,” but “appearances are deceptive”; Caroline Reveillaud, an artist and researcher, attempts to examine the mechanisms of seeing and our perceptions for her third solo exhibition at the Florence Loewy gallery.

Titled Sharp-eyed, in this exhibition the artist above all puts her own perception – an introspection – into perspective, with hindsight. Seeing is first contextualizing who we are and where we come from. Whether we are disabled or not, a minority or not, and according to our origins (social, educational, etc.), everything can absolutely change in the ways in which we apprehend the world. Seeing is therefore above all situating ourselves.

Here, Caroline Reveillaud rewinds the thread of the construction of her vision and her artist’s eye. She particularly lingers on the images of artwork reproductions that she has come across throughout her artistic career, in magazines for the general public, specialized revues and dedicated books. Very normative and calibrated, these photographs of artworks that pound our collective imaginations are in the line of the botched attempt at neutrality of the White Cube. In a mise-en-abyme process and a determination for emancipation, Caroline Reveillaud decided to photograph these ersatz prints in CMYK (cyan, magenta, yellow and key/black). More specifically, it is important to her to scrupulously photograph the reproductions of iconic, two-dimensional, pictorial works, obsessively on the lookout for their slightest defects. The excessive use of the flash and the zoom, the appearance of the (four-color) screen, the shininess of the glazed paper, the perspective and optical blurs, the printing defects, everything that can reveal the artificiality of these images of images becomes their principal subject. The glitch, the bug, the mistake are placed in the center of these new replicas. Bathed in a juxtaposition of dots of color like a kaleidoscope, our expression is lost, our pupils dilate, our balance becomes unsteady, our fields of vision shift. The biological limit of our own perception (the eye’s separating power) is put to the test. We become cross-eyed.

This new collection of interchangeable reproductions, with truncated subjects whose temporality is uncertain, proposes that we leave aside our sense of analysis and reason to fully plunge into the materiality of the images. Texture, screen, touch, dot, grain, crackling, the sense of touch definitively prevails over that of sight: we want to touch! To grasp. Moreover, only a finger, the end of a hand, on the edge of the framing of one of these images of images, remains perceptible – like a wink of the fingertips.

Then, with that determination to go ever further in the deconstruction of these ex-icons, Caroline Reveillaud will put them in motion, give them form and life as though to definitively let them escape.

On one hand, the surface of these images is distended into space on an architectural scale. Raised and blow up, these photographs with dilated pores take on the status of an object and the form of steles. Through their relief with regular undulations, they bring to mind the construction materials of temporary living quarters or other shelters. Their surface punctuated with hollows and bumps deflects the impact of light and blurs a little more their readability that changes following the movement of our bodies in space. On the back side, their framework leaves room for shelves that refer to the vocabulary of the bookcase: those famous objects on which knowledge is arranged and piled up. Here, they are different building tools (ruler, compass, plumbline, etc.) that are housed on them recalling both the fabrication of these image-objects, but especially the instruments that served the knowledge of the world – not to mention its conquest. The front-back of these panel-screens functions as an incessant coming-and-going between construction, deconstruction and reconstruction.

On the other, Caroline Reveillaud calls on another visual limit: retinal persistence that made the appearance of cinema in 24 images per second possible. The still images are therefore put into motion in a video accompanied by a soundtrack and subtitles. The whole creates a sensitive, poetic and philosophical stroll on the different ways in which we see and perceive the real, and we build a history of vision, and forms a parallel with the history of art and that of science. Written in the first person, this narrative is a visual journey devoted to destabilizing our supports and acquired knowledge. Disoriented, in a state of vertigo, in the end it is an atomic vision of the world that Caroline Reveillaud offers us: precisely where seeing and being blend into a heap of functional or dysfunctional colored dots. A chaotic vision.

Blind? Without presupposed vision: blind! After having exhausted the sense of sight and that of touch, Sharp-eyed turns to that of hearing. Rhythms, then a voice guides us in this meander inside the images. A voice echoing the artist’s reflections illustrated by stories and scientific experiments on the comprehension of the mechanisms of sight. A monotonous voice on a repeated rhythm gradually leads us to a form of trance close to the autosuggestion used in hypnotherapy. We let ourselves be guided, we let ourselves be carried, in this linearity that evokes the writing of any history/story. But here, once again, if we are attentive enough, we will hang on to the arrhythmias, the mishaps, the tears in the frame, the bugs, the glitch.

Open your eyes − wide open: Look up!

Alexandra Goullier-Lhomme